In a bid to recover the trade lost to road traffic the journey

from Audley End to Haverhill was reduced from 37 minutes to 31, and it

was hoped that the new diesel trains would help to balance the books by

cutting costs.

All was in vain, however, and, since individual lines now had to show

that they were ‘viable’, the writing was very much on the

wall. Ironically, one of the ways that British Rail tried to save money

was to run fewer trains, which, in turn, provided an even poorer service!

At the time of the introduction of the railbuses, the then Chairman of Haverhill UDC, Mr R C Poole, welcomed the new, better trains but pointed out that the service was now reduced to only two down trains for Haverhill, and called for the consideration of a better means of travel to London.

The plea fell upon deaf ears, and, in April 1965 the British Railways Board gave notice of their intention to close the line from Marks Tey to Cambridge, with total closure planned for 31st December 1966.

Railway closure had always been unpopular (even the odd one in the 19th century) but the steady stream of railway closures, gathered pace during the 1950s, and turned into a veritable torrent during the following decade, when the railway network was “rationalised” by the infamous Dr Richard Beeching, chairman of British Rail from 1961-1965. In March 1963, Lord Beeching produced his report, The Reshaping of British Rail, which proposed the closure of one-third of Britain’s 18,000-mile railway network (mainly rural branches and cross-country lines), and the closure of some 2,128 intermediate stations on lines that were to remain open.

Because of its low population density, East Anglia suffered more than most regions, and most cross-country routes and branch lines disappeared. Overall the figures are quite stark. In 1955, British Rail had 20,000 miles of track and 6,000 stations. Twenty years later, this had been reduced to 12,000 miles of track and 2,000 stations – roughly the same size as we see today.

HAVERHILL AND THE AGE OF STEAM

By Ian Hornsey - Part 2

So much soil was needed to build the embanked approaches for the Sturmer arches, that, with no spoil available from other works, their construction caused a large depression to be left nearby, and the resultant crater was later to become known as ‘Junction Hole’

In the Cambridge direction, GER trains called at Bartlow,

Linton, and Pampisford, before joining the same company’s London

to Cambridge line at Shelford. In the Sudbury direction, the intermediate

stations were: Sturmer, Stoke-by-Clare, Clare, Cavendish, Glemsford, and

Long Melford (from where travellers could reach Bury St Edmunds via Lavenham,

Cockfield and Welnetham).

Being larger and more convenient, Haverhill North was to prove more popular

with the travelling populace than Haverhill South and even the CV&HR

made use of it once the necessary connections had been made.

A pub, the Prince of Wales, was built next to North station, and was a firm favourite with railway passengers for many years. Although the station itself was well used, Station Road and the yard in front of the station was unpaved and usually knee deep in mud during winter months. It was as late as 1890 before even a cobbled and brick path was laid to the booking hall entrance, although the rest of the yard remained untreated and muddy. The following year, Haverhill North railway station was given a footbridge over the railway line and steps were built down to Wratting Road.

Sturmer Arches

In the same month that Haverhill was linked to Sudbury (via Clare and

Long Melford), a rail link was established between the CV&HR line

(by now generally referred to as the ‘Colne Valley line’)

and the GER line, thus enabling the former to reach Cambridge at last

(albeit not via its own metals).

This involved the building of a three-arch viaduct over

the Sturmer Road. Locally known as the ‘Sturmer Arches’, the

structure was originally called ‘Junction Bridge’, and is

a landmark until this day.

The linking section is 70 chains in length, and the crown of the central

arch 25 feet above the road. The link was three-quarters of a mile short

of Haverhill South, and joined the GER a quarter of a mile east of North

station. So much soil was needed to build the embanked approaches for

the arches, that their construction caused a large depression nearby,

and the resultant crater was later to become known as ‘Junction

Hole’.

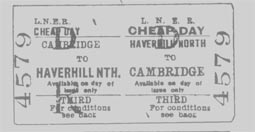

The railway brought with it much greater prosperity and

freedom. Not only could goods be moved about freely but people as well.

For the first time in their lives local people could go on day tips to

places they had never been before. They could take a day return to the

seaside.

A treat undreamed of by their parents.

A revolution was happening not just to transport but to the every- day lives of working men and women. The demand now was for faster and cheaper transport.

As the railways grew it was decided to amalgamate the many

small companies into four large companies (the ‘Big Four’).

The actual process of ‘grouping’ took place on January 1st

Jan 1923 and the numerous East Anglian lines, which were dominated by

the GER became part of the London and North Eastern Railway (LNER), which

was the second largest, in terms of route miles, but also the poorest.

The ‘Big Four’ mergers resulted in much rationalisation, and

the following year (July 14th 1924), Haverhill South railway station in

Colne Valley Road was closed to passengers, who were then compelled to

use Haverhill North instead.

From the beginning of the 20th century, all CV&H trains from Halstead were using North station, except for the last train of the day, which terminated at South station. The last passenger train over the CV&H line to Haverhill left Marks Tey at 7.15pm on 31st December 1961. The LNER lasted for approximately twenty-five years until the railways were nationalised in 1948, whence it became a constituent of British Railways (Eastern Region).

Unfortunately, many rural stations were badly sighted, and

well away from the towns and villages that they purported to serve. This

led to a rapid decline in passenger numbers when more convenient forms

of passenger transport became available.

Various measures were taken to reverse this decline in the Haverhill area,

perhaps the most revolutionary being the introduction, of diesel railbuses

on the Saffron Walden branch line, serving Haverhill, Bartlow and Audley

End.

Today Haverhill is one of the largest towns in Britain without a railway station. The old railway lines are gone and the once busy embankments have been replaced by quiet countryside walks. Here and there the old bridges can be seen and the Sturmer arches are still visible to visitors entering the town centre from the west. The mighty steam trains that brought Haverhill so much prosperity have been replaced by cars and trucks.

The Future?

With the ever-changing economic climate, railways may again prove to be

a viable proposition, and with this in mind, the Cambridge to Sudbury

Rail Renewal Association (CSRRA) was formed in 1995 to raise the issue

of re-instating the railway from Cambridge, via Haverhill to Sudbury.

Since then the group has grown to around 150 people the ultimate aim being to develop rail services, including passenger and freight, on the former Stour Valley between the old GER mainline at Colchester, along the current branch line to Sudbury, and then onto Haverhill before joining the Liverpool Street to Cambridge line at Great Shelford.Support for the line is strong, and petitions which were organised in Cambridge, Haverhill, Clare, Long Melford and Sudbury were signed by over 11,000 people. Stage one of the feasibility study showed that around 73% of people surveyed would use the railway and another 16.2% said they might use the railway. In the light of the approved planning permission for the new Tesco store, if the rail project does succeed, the new company will not be using Haverhill North station!

It can be argued that only the Agricultural Revolution had a greater influence on our general landscape than did the coming of the railways. Whether or not trains still run, much of the work of those gangs of Victorian navvies will be seen for as long as man continues to inhabit these islands; the ‘Sturmer Arches’ are a good case in point.

The old North

station site is now the proposed site of the new Tesco superstore.

Once again the site will be busy but this time it will be with visitors

wanting to buy their groceries rather than to catch a train to the seaside

Abandoned North Station in the 70s